|

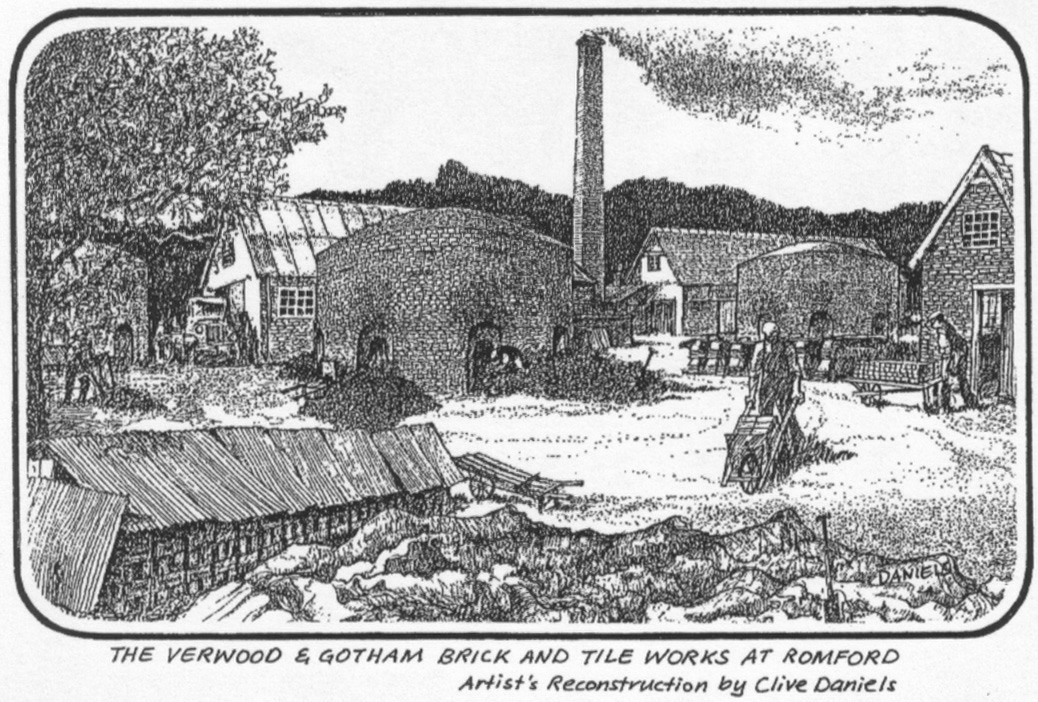

Gotham Brick & Tile Company Works.

|

This

brick and tile yard was situated in Romford on the western

edge of Verwood in Dorset in the UK. It is now derelict and

it was fortunate to be able to see the kilns and chimney as

they were gradually demolished. It is a sad thing that all

evidence of a brickyard has virtually gone for ever.

Mr. Waters was the

only tile maker still living in the village in 1967. He came

with his father and brothers, a family of tile makers from

Sussex

to boost the output of tiles in Verwood. He was delighted

to talk of his work and could not resist illustrating his

memories. Mr. Waters was the

only tile maker still living in the village in 1967. He came

with his father and brothers, a family of tile makers from

Sussex

to boost the output of tiles in Verwood. He was delighted

to talk of his work and could not resist illustrating his

memories.

Apparently

yellow and brown, clay was dug on the site, these clays

producing good red bricks. Three parts clay and

one part sand were mixed with water in the pug mill until

the mixture was like putty. It was left to stand for one

day. In the early days, bricks were made in a

mould by hand or in a presser which pressed out one brick at

a time. In later years a cutter which cut four housebricks

at a time was attached to the outlet of the pug mill, and I

understand that another attachment could be fitted for

making drain pipes. Fie-place bricks were also made.

The pug for tile making was made much softer

than that for bricks and was taken from the pug-mill in

large chunks to be made into tiles by hand. As Mr. Waters

said he "had to have a system" to make tiles

rapidly without wasted time and effort. The pug for tile making was made much softer

than that for bricks and was taken from the pug-mill in

large chunks to be made into tiles by hand. As Mr. Waters

said he "had to have a system" to make tiles

rapidly without wasted time and effort.

The picture shows the buildings

that housed the "pug-mill" and other brick making

equipment.

The

clay was placed on the right hand side of the work-bench, a

box of sand on the left and the tile mould, made of wood or

iron, placed on a piece of oak in the centre. When the mould

and base were sanded, a lump of clay was cut and thrown into

the mould the top being cut level with a wire

"bow". This surface was smoothed level with a

wooden striked dipped in water, which was used in two quick

strokes. The mould was then lifted off the tile

which was placed on the sanded floor. Mr. Waters

informed me that this method of tile making is the

Staffordshire method.

The

tiles were then dried on racks until they were leather hard

when they were bevelled on a "wooden horse". Five

tiles were placed on top of one another on the horse and the

wooden top was pressed on top of these. The

tiles were then stacked in piles of five on the drying shed

floor until bone dry, this stage was called

"checkering". The tiles were then

fired at the same time as the bricks.

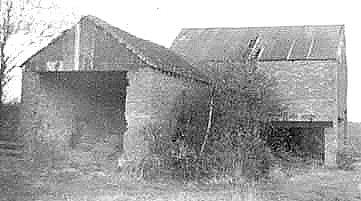

"The pictures show the

Belgium Kiln, Exterior and Interior."

The

kilns used during Mr. Waters' time were circular Belgian

type kilns with firing holes at intervals all round and one

entrance used when stacking and removing bricks and

tiles. Apparently before 1924 square Scotch

kilns were used. These were twelve feet high with six firing

holes along each side and an entrance hatch at each end. By

the descriptions

I

have heard they had no roof, the top bricks were watched

during the firing to judge the heat obtained. These top

bricks the "plotters'' also kept the heat in.

The pictures shows the remains of a Skotch

kiln.

The bricks were

stacked in the bottom and at the sides of the kiln and the

tiles stacked within them. As Mr. Waters

explained, the tiles were stacked on their bottom edges so

that the lip at the top kept the tiles apart, allowing the

heat to travel between them. The firing with coal, took two

days and nights the fires being checked every two hours. The

draught was drawn up from the firing holes and then down

through a central pillar in the kiln, under the drying

sheds, through flues and up through an eighty feet high

chimney. During the firing "the bricks

became nearly white hot". The bricks were

stacked in the bottom and at the sides of the kiln and the

tiles stacked within them. As Mr. Waters

explained, the tiles were stacked on their bottom edges so

that the lip at the top kept the tiles apart, allowing the

heat to travel between them. The firing with coal, took two

days and nights the fires being checked every two hours. The

draught was drawn up from the firing holes and then down

through a central pillar in the kiln, under the drying

sheds, through flues and up through an eighty feet high

chimney. During the firing "the bricks

became nearly white hot".

The

entrance hatch was bricked up during firing, but one brick

was left loose so that three half-tiles which had been

placed in a certain position could be pulled out with a

hooked iron rod for testing. When firing was complete the

kiln was left to cool.

Most

of the tiles were a "natural red", others were

coloured, the colouring being mixed with sand used at the

moulding stage. Manganese with sand produced black tiles;

manganese alone gave a purple colouring and a mottled effect

was obtained by sprinkling manganese over the tiles after

they had been sanded. When green tiles were

required, the tile makers had to tour the nearby fields

collecting fresh cow-manure. This was made into a solution

with water and manganese and was painted onto the surface of

the tiles.

A

variety of different shaped tiles were made including the

normal tiles, one and a half tiles, half tiles or slips,

eave, ridge, hip and valley tiles as well as decorative,

wall tiles.

Until

1910 the bricks and tiles were taken to the surrounding

villager, and towns by horse and cart, the number of bricks

per load depending on the size arid ability of the

horse. Some horses could pull as many as three

hundred and fifty to four hundred bricks. After 1910 the

bricks were

transported by Foden's steam lorries and could be taken

greater distances. I understand that the' roof of

Bournemouth Pavilion is tiled with Verwood tiles.

Mr.

Waters said that he made an average, of four thousand tiles

per week for which he was paid thirty two shillings. He was

reminded by his wife that he always worked on Sunday

mornings, for which he was paid no extra. He and his family

made tiles in Verwood for fifty years, until the outbreak of

the second world war.

Mr-

Waters - a craftsman at heart - enjoyed inventing in his

spare time and made some beautiful model ships from rough

wood and "odds and ends" as he called them.

Copyright © P Reeks.

|